Black History Month feature - Frederick Douglass in Scotland

Published on 28 October 2021

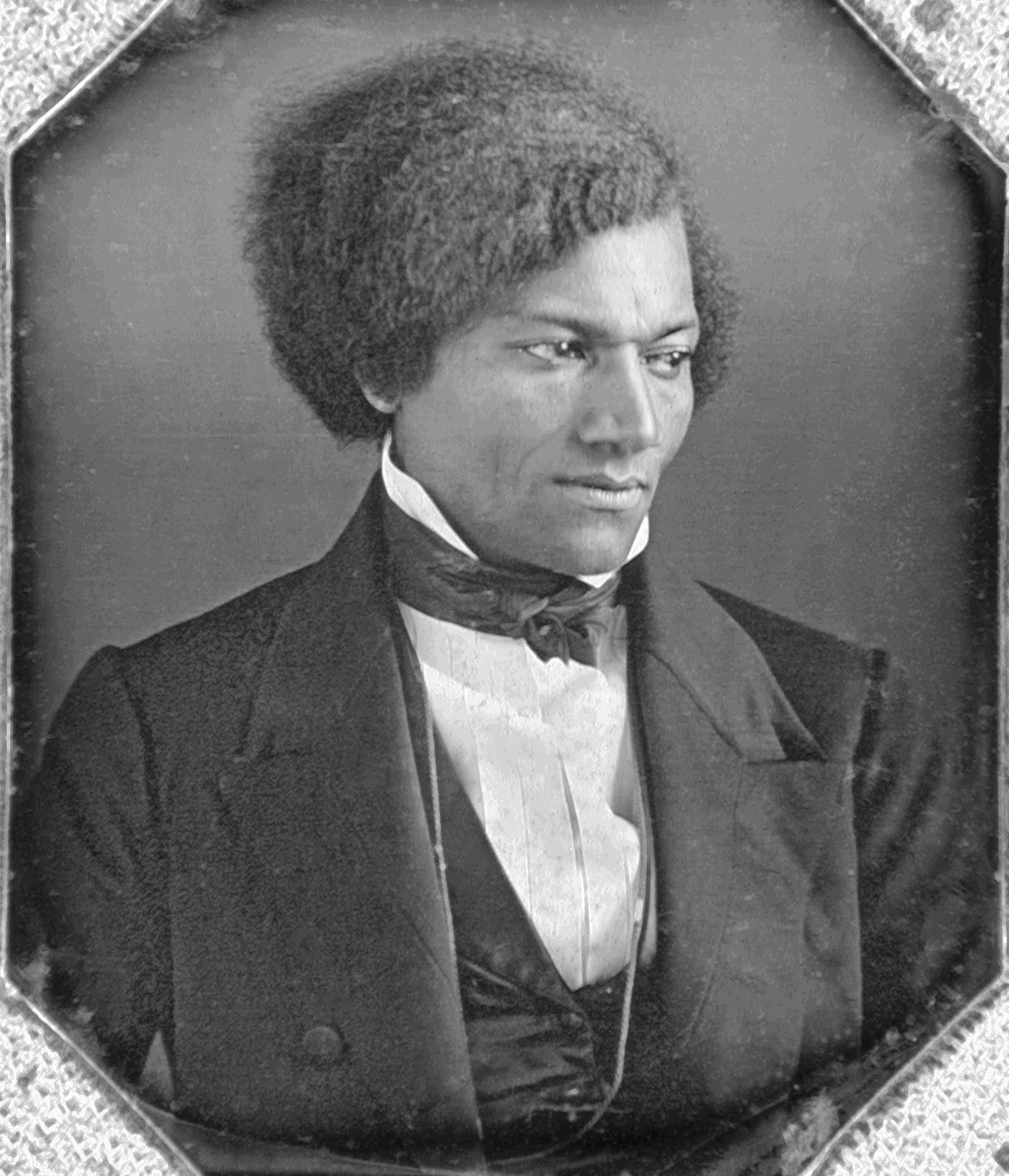

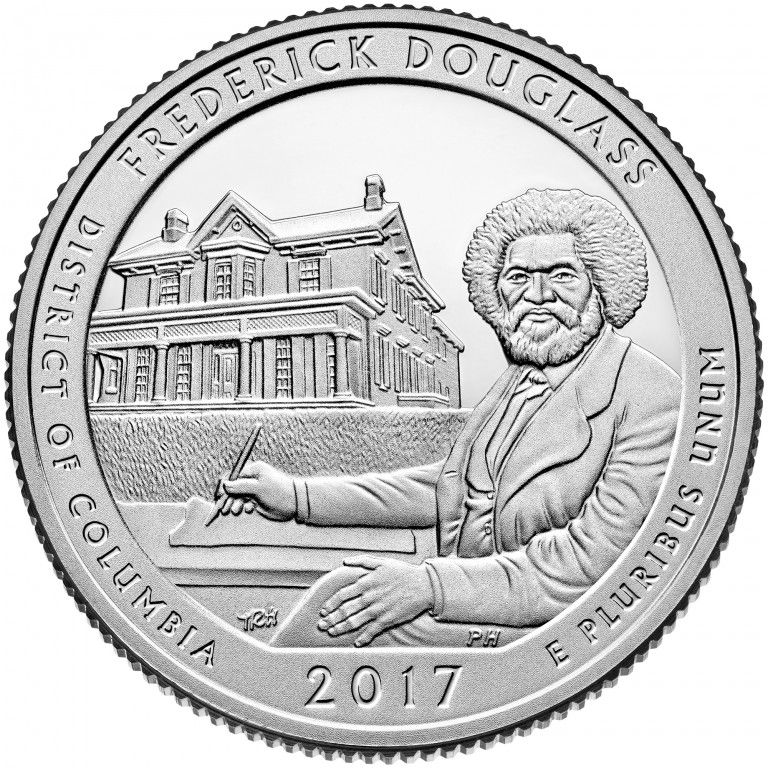

As Black History Month comes to a close we take a look at the life of the American writer, preacher and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who visited Scotland 175 years ago and made an impact on both the country and the Church.

Who was Frederick Douglass?

Born into slavery in Maryland around 1818, Frederick Douglass made a daring escape at age 20 and became one of America's foremost anti-slavery activists. His mother Harriet Bailey was enslaved and his father was an unknown white man, often thought to be his ‘master'.

Separated from his mother as a baby he was taken away from his grandparents at age six. In secret, he taught himself to read, discovered the Bible and converted to Christianity at age 13. At Sunday worship, Frederick defied local slaveowners by teaching other enslaved people to read the New Testament. Contracted out to a farmer, he was brutally whipped and beaten, leaving him scarred for life. The beatings ended at age 16 after he rebelled and fought back.

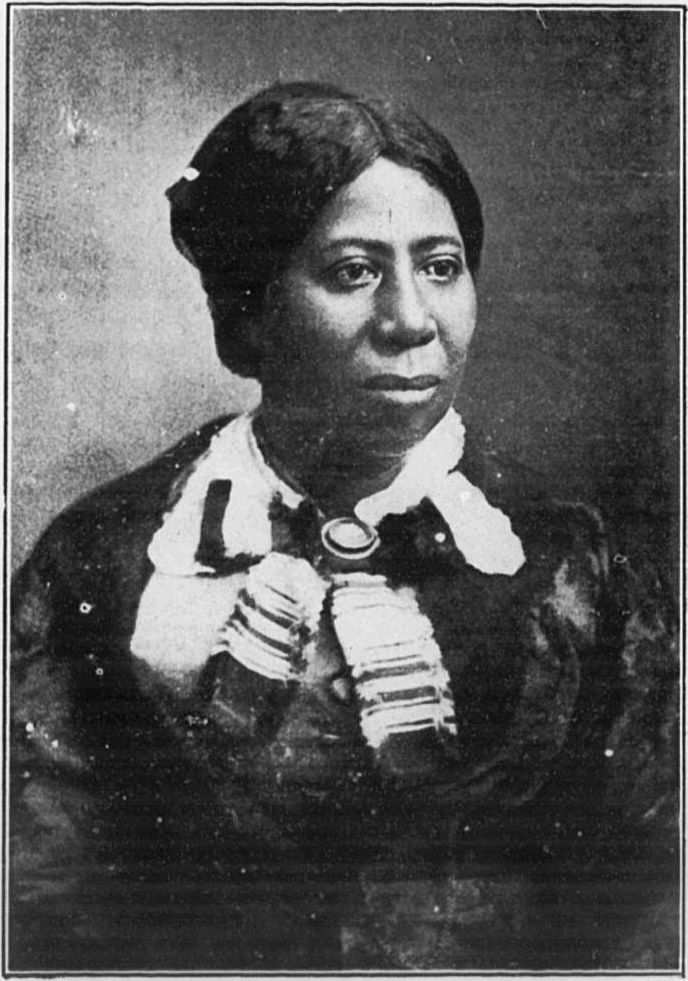

In Baltimore, he met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free woman. Soon after, he left the city and took a risky train journey to the North using identification papers belonging to a free Black seaman. On finally reaching New York and freedom Douglass wrote: "A new world had opened upon me… I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life."

Frederick and Anna married taking the name Douglass, based on characters in The Lady of the Lake, a poem by Walter Scott. An active member of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, in 1839 he became a licensed preacher. After sharing his story at abolitionist meetings, Douglass was asked to become an anti-slavery lecturer and spoke in meeting halls across the north, braving opposition and at times violence.

In 1845 he published his autobiography, one of three versions he wrote at different times in his life. His book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave quickly became a best-seller. Now famous Douglass faced an increased risk of being kidnapped and forcibly returned to slavery. So with the help of friends and supporters he set sail for Liverpool where he began a speaking tour of Britain and Ireland. He was not yet 30 years old.

How Scotland profited from slavery

During his visit to Ireland and Britain, Douglass could sit at the same tables and attend the same churches as white people. Yet he also saw extreme poverty that reminded him of how slaves were treated. And he discovered that Britain's relationship with slavery was not at all simple.

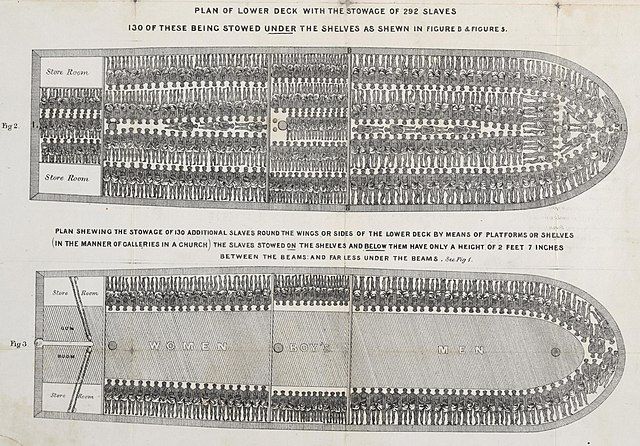

During the 1700s and 1800s people across Britain amassed wealth from the transatlantic slave trade and from the sugar, cotton and tobacco produced on Caribbean slave plantations.

In his book Scotland and the Abolition of Slavery, author Rev. Iain Whyte explains that in the late 18th century Scots owned more than a quarter of the estates on Jamaica as well as property on other Caribbean islands. Other Scots were involved in trade to the islands or worked there as lawyers, bookkeepers, doctors, carpenters and clerks. There were many Scottish people who defended the slave trade and slavery. Some wealthy Scots also brought enslaved people to Scotland where they were forced to work as servants.

In 1778, after being refused permission to live with his wife, a man called Joseph Knight challenged his "owner" by walking away from captivity. After a legal battle, the Court of Session ruled that slavery was not legal in Scotland.

However, that did not prevent Scottish people from owning slaves overseas. In 1796, Mr Whyte says, Scots owned 30% of the estates in Jamaica and by 1817 a staggering 32% of the slaves.

Yet Scotland's role in slavery was barely acknowledged until quite recently.

Christians push for abolition

Africans who had endured the horrors of slavery began telling their stories –challenging the false claims that slaves were treated well—and an anti-slavery movement that included men and women from all walks of life began to form in Britain.

By the 1780s abolition societies from across Britain were petitioning parliament to end the slave trade, and a third of those petitions came from Scotland. In 1807 the British Parliament officially abolished the slave trade

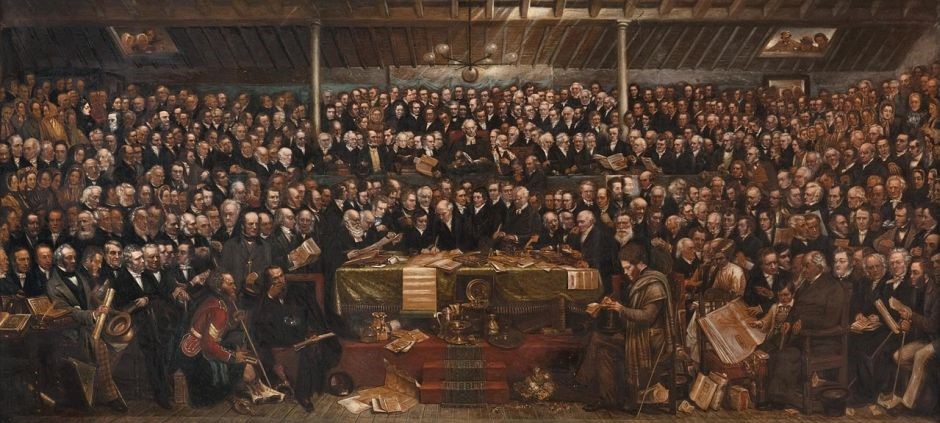

Rev Iain Whyte tells how the campaign to abolish slavery itself started in 1823 and grew in strength between 1830-1831. Throughout the campaign Christians from all denominations, including parish ministers, were at the forefront of the movement.

"Church of Scotland congregations, presbyteries, and synods were pioneers in opposing the slave trade in 1788, though by 1792 they were joined by many other bodies," Mr Whyte says.

"The Church of Scotland was represented by congregations and presbyteries who petitioned alongside other churches, although the Church of Scotland as a body never actually sent a petition to Parliament from the General Assembly or the Moderator.

"Campaigners did attempt to get the Assembly to do this in 1788 but were resisted by the Moderator on grounds that it was below the dignity of the church to petition parliament. Instead it was mentioned in the Loyal Address to the King.

"Deliverances opposing the slave trade were passed in 1788 and 1792, but in 1830 when many Presbyteries and Synods petitioned to abolish slavery, the General Assembly did not discuss it.

"By the 1830s slavery had become the leading moral issue in Scotland and the majority of people believed that slavery was a sin."

Finally, in 1833, slavery itself was abolished across the British Empire, setting free 800,000 people— although the law had a built-in delay of four years. At the same time the government paid out compensation of £20 million to 46,000 slaveowners, a massive sum equal to between £16 and £17 billion today. Former slaves on the other hand were not compensated.

Frederick Douglass in Scotland

During 1846 Frederick Douglass toured the country packing churches and halls from Paisley to Aberdeen, speaking about the cruelty he had endured as well as telling the stories of other enslaved people. He wrote warmly of his reception saying in Scotland he was "treated as an equal man and a brother".

His fiery speeches and personal charisma inspired people and he was appointed "Scotland's anti-slavery agent". His goal was to raise support and funds for the American abolition movement, but he also joined a local campaign that involved the newly formed Free Church.

Send back the money

Just three years before Douglass arrived in Scotland, the national Church had split apart in a 60/40 division that was to last more than 50 years. The conflict was over the spiritual independence of the church and a secular law that allowed landowners to choose parish ministers.

After a court ruling stated that the Church of Scotland had been established by the state and gained its legitimacy from parliament, a group of evangelicals urged the Church to reject its government funding and reclaim the right to manage its own affairs.

Finally a breakaway group of 450 evangelicals left the church and formed the Free Church choosing as its first Moderator Thomas Chalmers, whose statue stands near the Church of Scotland offices in George Street, Edinburgh. The split was known as the Great Disruption.

The problem for the Free Church ministers was that in leaving they had to give up their manses, their incomes and their buildings. With no money to support the breakaway church, they appealed to sympathetic American churches for help. Their appeal raised around £3,000, but it came from slave-owning Presbyterian churches in the Southern states.

Many Scots felt that accepting the money meant the Free Church was supporting slave-owners and Douglass became the figurehead for the campaign, which was calling on the Free Church to ‘Send back the money.'

The issue was divisive and while Douglass was greeted with cheers in many places, he was also locked out of a hall by Free Church deacons. For Thomas Chalmers and other Free Church leaders it was a moral dilemma they were not ready to face and the money was never returned.

After 1846: the struggle continues

While he was in Britain, money was raised to buy Frederick Douglass his freedom. He was asked to stay in Scotland but he went back to Anna and their four children to continue the struggle for freedom in America, although he did return to tour Scotland again in 1859. Douglass founded a weekly newspaper, the North Star, whose motto was "Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren."

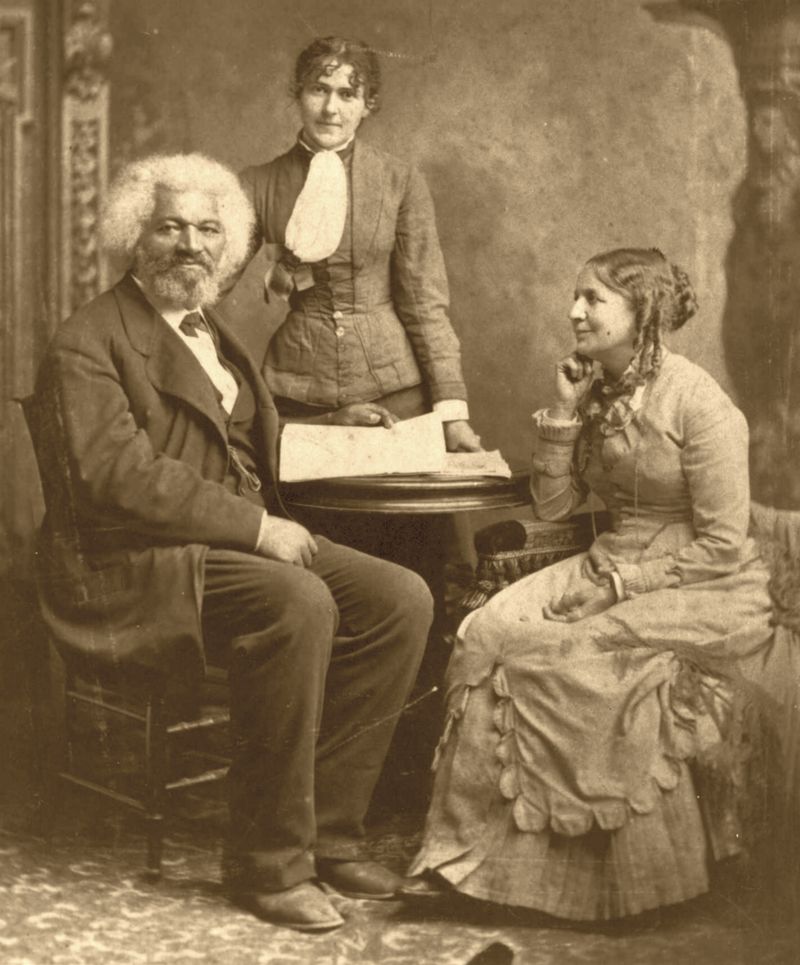

The campaigner went on to become a leading politician, a supporter of women's suffrage and a key figure in the anti-slavery movement. Frederick and Anna were also part of the Underground Railroad and sheltered hundreds of escaping slaves. The couple had five children. Two years after Anna's death in 1882 Frederick married again to a white suffragist Helen Pitts.

The split between the established Church of Scotland and the Free Church was eventually healed in 1929 after the Church's autonomy was confirmed in the UK parliament.

Legacies of Slavery

The General Assembly of 2020 asked the Faith Impact Forum to research the Legacy of Slavery within the Church of Scotland. That work is underway. The forced displacement of between 12 and 12.8 million Black Africans to the Caribbean and America through chattel slavery is one of the darkest episodes in recent history and the repercussions of the transatlantic slave trade continue to affect people living now.

The Legacies of Slavery project group is working to learn more about and understand the relationship between the Church and slavery during the 17th to 19th centuries, and how it still affects people today. The group is also undertaking work to document physical memorials to individuals connected to the transatlantic slave trade contained within Church of Scotland buildings. The Church also supports work on ending modern-day slavery and human trafficking.